Hands On Indonesia

By Emily Bruell

The first hand I remember seeing in Indonesia was a taxi driver’s as he lifted my bulging backpack into his taxi’s trunk outside the Medan Airport. I stood, along with eleven other 18 and 19-year-old students, in the sort of bleary-eyed stupor that accompanies 24 hours of travel to the literal other side of the world. We had signed up for a three-month gap semester program traveling Indonesia’s islands in an effort to expand our worldview and come to understand more about culture, community, and conservation on the archipelago. I was sure that the emotions I’d felt at the beginning of our marathon travel day — curiosity, excitement — were still somewhere inside me, but then all I felt was exhausted and sore.

I rolled my shoulders, relieved of the weight of the backpack, and studied the man’s browned hand as he grasped the strap of another bag. I’d thought it was just sleep-deprivation, but — no, there it was — his left pointer fingernail was half an inch long. “Do you see that?” I whispered to someone (names at that point were a tangled, unmemorable mess). “The fingernail?” she replied. “Sometimes the drug addicts in San Francisco will do that, for coke— you don’t think he’s a drug addict, do you?” I shrugged. All I knew was that the night air was stiflingly hot, the mosquitos whined threats of malaria, and I felt very, very far from home.

***

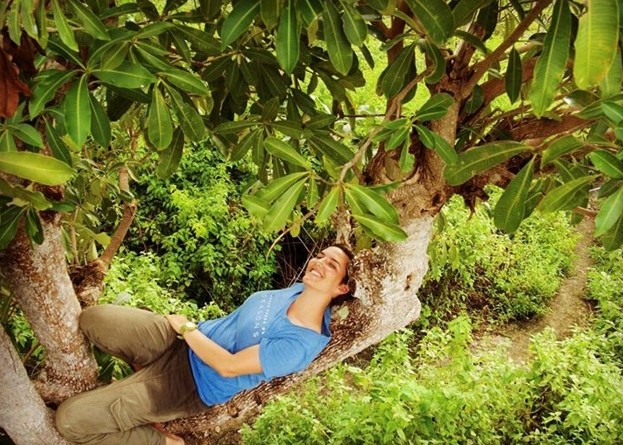

Fast forward to another hand, this one offered to haul me over the trunk of a fallen tree in the Sumatran jungle. I’d overcome my jetlag and learned — after working up the courage to ask Sapri, our Indonesian instructor — that the long fingernail was merely an expression of style, and that drug use rates in Indonesia are less than a quarter of the user rates in the US. Now, we were trekking through the thick jungle vegetation in search of wild orangutans.

I was doing my best to make peace with the venomous centipedes that scuttled along tree roots like flattened, many legged sausages and the unreasonably sized cicadas that sailed, shrieking, through the air. I told myself: I am calm. I am serene. It was (I had to admit, after panicking over a spider on my head that turned out to be a leaf) not going well.

It is probable that this discomfort showed on my face, because as our guide Yohan gripped my hand and pulled me effortlessly over the log, backpack and all, he asked: “You okay?” I nodded, embarrassed to have interrupted his conversation with my instructor. He wasn’t a scientist and had never gone to college, Yohan was telling her, but he thought a recent scientific journal article published about the life expectancy of orangutans must be incorrect.

Based on gestation time and frequency of pregnancies in the orangutan community, he explained, the published life expectancy would lead to population growth at only half the speed he had observed (1). He plunged confidently through the undergrowth, following circuitous, overgrown trails in search of orangutans, and we stumbled along in his wake. “How do you know where you’re going?” I asked in amazement as we crested a ridge and cut diagonally down it. Yohan paused and turned back to me, hand held up to his lips in preparation to make a smooch-like orangutan call. “It’s my home,” he said.

***

Two weeks later, we’d left the smoky jungles of Sumatra for the jumbled tin roofs and tangled streets of urban Jogja. I was sitting on the living room floor of my first homestay house while Pak Udin, my host father, shaped my fingers on the guitar neck to play a G chord. We hadn’t interacted much before this; with his heavy brow and quiet demeanor, he cut a rather intimidating figure, and his English was as rudimentary as my Indonesian at that point.

But something about plucking out chords on the guitar seemed to soften the intense set of Pak Udin’s face, and our shared purpose of music motivated us to push through the language barrier. We mangled pronunciations. We mutilated grammar. Several times he abandoned language altogether and reached over to correct my finger-positioning by hand.

More than once, I saw him wince in a visceral reaction to a malformed chord. But by the end of the evening we’d made it through the traditional children’s song Satu Satu — singing and playing in unison — and he called my host mother and siblings to come to the living room to hear us play. A few afternoons later, we had another lesson, and this time he asked me to pick an American song to teach him. “Mungkin minor?” he suggested. Maybe in a minor key?

“Greensleeves?” I offered. I pulled the song up on You Tube, a little uncomfortable. Outside the open window, the crows of roosters mingled with the melody of the call to prayer. Playing from tinny phone speakers, the old English song felt awkwardly alien to this place — irrelevant. On Pak Udin’s guitar, though, the melody became something more. He blended in the trills and tremolos that adorned his usual playing, transforming the once-trite tune into something strange and lovely. The next morning, I woke up to the familiar melody floating into my bedroom: “Indonesian Greensleeves.”

***

Several flights and a winding, 8-hour bus ride later, I found myself in Langa, a small village in the mountains of Flores Island. I’d heard that I’d be placed in a homestay with a younger sister, and I assumed that she’d be similar to my host sister in Jogja: sweet, quiet, and utterly shy for the first week and a half. Then I met Fania.

Small, perpetually runny-nosed, and four or five years old (depending on her mood when I asked), Fania has wildly curly hair and a spirit to match. She greeted me with a flood of conversation made unintelligible by speed and accent, and when I failed to respond while she paused for breath, she abruptly changed tactics. “Do you like chocolate?” she asked in Indonesian. I nodded; she shouted some rapid-fire Indonesian at her mother; a crumpled five thousand rupiah note was passed down to her; she seized my hand. “I will buy you chocolate crackers,” she promised, and proceeded to lead me through the village to a tiny shop.

For the next few weeks, walks like these — with Fania holding my hand and urging me to skip whenever possible — were commonplace. I possess a spectacularly bad sense of direction, and this arrangement saved me various times from getting lost. But there was another reason why these and other touches — daily high fives, thumb wars, and teaming up in one of the common neighborhood volleyball games in which Fania was so remarkably uncoordinated — meant so much: they tethered me. I was living on an island a hemisphere away from everywhere I’d previously called home, but I wasn’t lost in any sense of the word. Fania introduced me to everyone we met as “Big Sister Emily.”

In the end, this is the amazement that still lingers, stronger than any of the memories of crazy adventures or epic scenery. I came to Indonesia with the kind of privilege Indonesians would have every right to resent, and yet I was met every step of the way with smiles and sweet jasmine tea and hands offered to help me, teach me, and welcome me as family.

- World Health Programme Atlas of Substance Use Disorders.

Emily Bruell is an English major at Carleton College in Minnesota. She just completed a semester of travel in Indonesia with the Where There Be Dragons gap semester program: three months full of new experiences ranging from climbing volcanoes and spray-painting street art to raising chickens and unclogging squat-toilets. Since returning, she’s encountered a not uncommon view of Indonesia: dangerous, poverty-riddled, unsanitary, and anti-Western. While the first three aspects are present to some degree, she hopes to bring attention to the limits of this narrow image of Indonesia and the incredible kindness, generosity and resilience it fails to capture.