An Oral History of the Day Women Changed Congress

By Lisa Chase

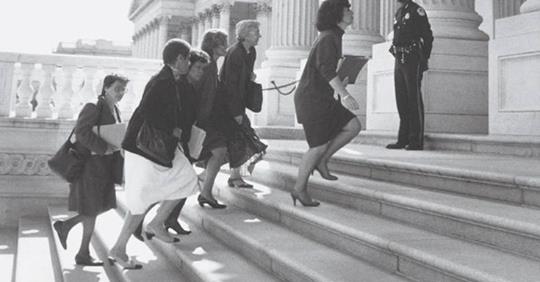

Photo credit: Paul Hosefros

When the handful of women in the House in 1991 heard that their colleagues in the Senate were refusing to let Anita Hill testify in the Clarence Thomas hearings, they charged over—and started a revolution.

On October 9, 1991, this photograph ran on page one of The New York Times. It captured a group of congress-women—Barbara Boxer, Nita Lowey, Eleanor Holmes Norton, Pat Schroeder, Jolene Unsoeld, and the late Patsy Mink, some of them in not-so-sensible shoes—running from the floor of the House of Representatives over to and up the stairs of the U.S. Senate, where, it turns out, they were not welcome.

“People call this photo ‘The female Iwo Jima,'” says Louise Slaughter, a Democrat from New York, now in her fourteenth term, who was part of the charge (but just out of the photograph’s frame). “It was a female uprising. Only they weren’t shooting at us.”

The woman for whom they charged was Anita Hill, whose allegations that then Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas sexually harassed her when they worked together at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission had just been leaked to the press. The Senate Judiciary Committee considering his nomination had barely hiccuped at the revelations; they were refusing to let Hill, then a law professor at the University of Oklahoma, testify. So one by one the women got up to protest the treatment of Hill by engaging in the “one minute”—a form of debate in the House in which members are allowed 60 seconds to pontificate on any subject.

About 30 seconds into Connecticut Democrat Rosa DeLauro’s one minute, all hell broke loose on the House floor (more on that later). While it did, seven of her colleagues decided to run over to interrupt the Senate Democratic Caucus lunch and plead for the Judiciary Committee to call Hill to the hearings.

Almost every woman on the stairs has a copy of this photo hanging on her wall. Boxer, since 1992 a senator (D-California), put it on the cover of her book Strangers in the Senate. Anita Hill has a copy too; she has kept the newspaper from the day the photo, by Times photographer Paul Hosefros, appeared.

“It was a metaphor for everything that was to come in the 1992 election cycle,” says Hill, now senior adviser to the provost at Brandeis University and professor of social policy, law, and women’s studies. “This was a turning point for all of us.”

In 1991, there were 29 women among 435 representatives in the House and two women in the Senate; after the elections in 1992, what came to be known politically as the Year of the Woman, the Senate’s female membership more than tripled (to seven!), and the House’s proportion of women rose above 10 percent.

“One of the old bulls in the Senate [said] to me, ‘I really hope you’re happy. This is beginning to look like a shopping mall,'” recalls Schroeder, who retired from Congress in 1997. “When I got elected in 1972, I asked the Library of Congress how long before half of the House would be female. They said, ‘At the rate we’re going, 400 years.'”

With the House in striking distance of achieving 20-percent-female-membership—23 years after Anita Hill and 41 years after Schroeder entered Congress—we thought it was a good time to reconsider the events surrounding this photograph and to ask the women pictured to give us the backstory behind Hosefros’ lens.

Rosa DeLauro (now in her twelfth term): It was October of 1991. I was a freshman; I’d just been elected in January, serving in my first term. Obviously we were all following what was going on with Anita Hill.

Patricia Schroeder: I had been very involved in sexual-harassment issues already, and also I’d had Clarence Thomas in front of me several times, as the head of the EEOC, and I was not too impressed. We were all shocked that they weren’t even going to let [Hill] come in and testify. We were told that Senator [John] Danforth had talked to [then] Senator Biden at the gym and said, “Let’s get my guy [Clarence Thomas] in.”

Louise Slaughter: And Danforth was an Episcopal minister.

Schroeder: Biden had promised Danforth that it would be a quick and fast hearing. I was really incensed, and I made a one-minute speech. In the House, any representative is allowed to make a one-minute speech.

Barbara Boxer: We went one after the other after the other. Well, Rosa DeLauro mentioned the word Senate in her one minute—in those days you had to say “the upper body”; you weren’t allowed to say the word Senate. So Rosa just said “Senate,” and one of the Republicans said, “Violation of the rules!”

DeLauro: All the proceedings in the House stopped. I think I had 28 or 30 seconds of my minute left. I just stayed at the podium. And pretty soon Dick Gephardt and Tom Foley [the House majority leader and speaker] came to the floor. I thought, ‘Oh my God, what have I done?’ The parliamentarian ruled I was out of order. There was a 15-minute vote to see if I could continue.

Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-Washingon, DC, in her twelfth term): Meanwhile, the [Senate] Democrats were meeting, and we had no reason to believe they were going to make the right decision. By the time we got through ungagging Rosa DeLauro, the meeting could be over, the Democrats could be scattered.

Boxer: Schroeder came up to me and said, ‘We have to have a plan here. Why don’t half of us go to the Senate and half of us stay here and make sure Rosa doesn’t get her words [stricken].’ I said, ‘Okay, let’s go.’

Schroeder: We all kind of fired ourselves up and went over. It was a very spontaneous thing.

Holmes Norton: It was spur-of-the-moment. It was a desperate move, a bunch of women, small in number….

Schroeder: We were like this little bevy of female grrrrrrhrhrhrhrhrahraharah. We knew they were meeting and were like, ‘Let’s just go.’

DeLauro: George Stephanopoulos was working for Dick Gephardt, and Georgie and I took the last 30 seconds of my speech and reworked it so I could get my point across without jeopardizing my one-minute. [The Democratic caucus lunch] could have gone unnoticed except for the Republicans calling attention to the one-minute. They wanted to cut off the debate, but what they did was prolong the debate, and the news media, who were around, started to get wind of it.

Schroeder: I may have called my press person and said, ‘We’re going to walk over to the Senate,’ and she may have made some calls….

Slaughter: Pat is a formidable woman.

Paul Hosefros (The Times photographer): When it came time for the Thomas-Hill story, you could say I was primed. I had covered the hearings—I may have been the only photographer to get the moment when Thomas kissed his wife.

Boxer: So we leave the House floor and there are 25, 30 cameras taking our pictures; we get to the steps and we realize they’re having lunch at the LBJ room. We get to the top of the steps….

Nita Lowey (Democrat from New York in her thirteenth term): And the reception we got was astounding. We knocked on the door.… We fully expected to be let in.

Boxer: They said, “You can’t come in.”

Jolene Unsoeld (Democrat from Washington who lost her seat in 1994): The Democratic leader at the time was George Mitchell. I don’t know how they treated women in the Senate, but they weren’t respectful of us.

Boxer: We said, ‘What do you mean? We’re women with about 100 years of experience.’ But they said, ‘No strangers.’ It’s a term of art—strangers are anyone who’s not a Senator—but it sounded so terrible. I said to Mitchell’s female assistant, who was sent to see us, ‘If you don’t let us in—you see all those cameras down there? They’re going to wonder why we came back down.’ So Mitchell came out to meet with us.

Slaughter: He wanted us to tell the press how cooperative he’d been. We went into the back, to the hearing room, and told Senator Biden that Anita Hill had to speak. And she did.

Schroeder: What did this photograph accomplish? Thank you, press. We got tons of press, and women were furious. We were trying to slow the hearings down. If we’d gotten one more day, we would have stopped the nomination.

Boxer: I can see the determination in our bodies. It’s one of those photos.

Slaughter: We were so consumed with getting this woman to express what had happened to her. We knew that this wasn’t a woman who would make something up. It wasn’t in her character.

Boxer: Because we made that walk over to the Senate, there were hearings, and America saw the way Anita Hill was treated, saw that there wasn’t one woman on the committee, that only 2 percent of the members of the Senate were women. It set off a chain of events. Look at the Supreme Court, where there are now three women. Things have changed mightily.

Slaughter: I still respect the bravery that Anita Hill showed. She is a brilliant woman. Heavens knows where she could have gone. And look where he is.

Schroeder: Anita Hill has paid very heavily for testifying; it’s very sad.

Anita Hill: A lot of things happened after I went back to Oklahoma. I was under quite a siege from the Washington press corps. Some things went on for years after I left Washington. [She received death threats, and two conservative activists mounted a crusade to have her fired from her job or have the law school eliminated; she resigned in 1996.] But because a woman suffers doesn’t mean that she’s eternally unhappy.

At the same time, [just] because I’ve made the most of the many advantages I had, I don’t think we can brush aside the stress and the pain of the experience. What we need to say is that these things shouldn’t happen. We have to be very careful in how we interpret that I’ve landed on my feet. Because that doesn’t take into account what I might have done with that energy instead.

Source: ELLE magazine